This article is from the November 1956 issues of "The Pennsy" the employee magazine

of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company.

|

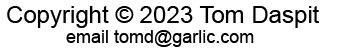

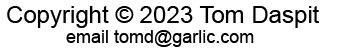

In the wind-whipped darkness, Sergeant Franklin A. Slack,

PRR Police, guards the reactor vessel at Marysville, near Enola

|

Reactor Vessel Heavy, High, Wide Travels Special PRR Route Six Days

Waybills never contain flowery words. The waybill on a special ten-car freight that rolled across the PRR last month said simply, "One power boiler and fixtures."

Actually, it meant the start of the Atomic Age for American industry.

Riding on a flatcar in the middle of the train was a huge steel cylinder called a nuclear reactor vessel. It will serve as the boiler of an atomic "furnace" for America's first full-scale commercial atomic power plant. Sometime next summer, this plant, at Shippingport, Pa., will begin converting the power of the atom into electric current for industries and domestic consumers of the Pittsburgh area.

"It'll always be proud memory for me that I hauled the first atomic reactor vessel through here," said Engineman Joseph W. Brewster as he piloted the train near the end of the route. "You don't wonder I'm being so super-careful."

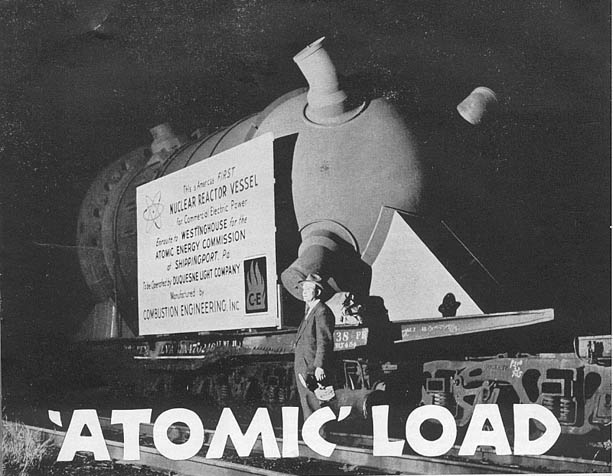

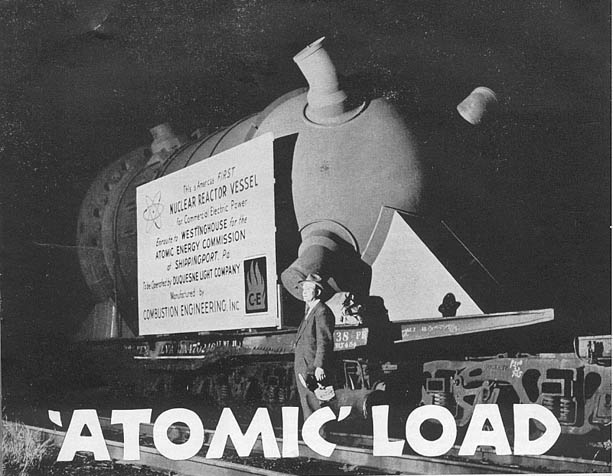

Roundabout route, made necessary by the high-and-wide load, ran to 529 miles, instead of normal, direct run of 391 miles

|

|

He was running the train then at 10 miles per hour. Extreme caution marked the whole movement. Fifteen miles per hour was top speed. At many overhead bridges and tunnels, the train came to a dead stop before crawling ahead. Half a dozen pairs of eyes watched every close clearance. Each night, the train was put in a yard to wait for daylight. A PRR police officer stood guard till it moved out.

From Hagerstown, Md., where the PRR move started, to Shippingport, 25 miles northwest of Pittsburgh, everybody was alerted to the crucial importance of this shipment-and to its special problems.

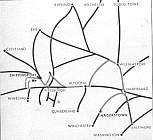

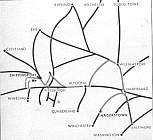

The atomic boiler was one of the biggest loads PRR men have ever handled: 12 feet 11 inches wide, 17 feet 7 inches high above the rails. There are bridges and tunnels and station structures that can't pass anything that big, so special routing was necessary.

The boiler wasn't exceptionally long 25 feet-but its high center of gravity, 7 feet 9 inches above rail, necessitated low speeds to avoid dangerous rocking.

Weight was another problem. The vessel, with its 8-inch-thick walls, weighed 153 tons. It required one of the PRR's stongest flatcars, the 24-wheel F -38. It also required elaborate blocking and bracing. A steel "cradle" was welded to the car to hold the vessel, which was further secured by steel tie rods and thick oak timbers. Total weight of the shipment, car, and dunnage reached 497,000 pounds. If a locomotive were coupled close to such a load, the concentrated weight might strain some bridges. To spread the weight, three empty flatcars were put between the locomotive and the F-38 car. Then three more empty flats were put behind the F -38 to provide extra braking power. In fact, there was only one other loaded car in the train-a gondola with 46,000 pounds of the giant nuts and bolts to be used in the reactor.

Hagerstown: As soon as load is delivered by the Norfolk & Western, it is precisely measured by Car Inspector J. R. Fouke, Gang Foreman G. E. Robinson, Helper W. A. Burnett

|

|

It was back in December 1954, that PRR clearance men began studying the problem of moving the big load. That was when the first inquiry about routes came from Combustion Engineering, Inc., builder of the atomic reactor. (The power plant to be served by the reactor is a joint undertaking of the Atomic Energy Commission; Westinghouse Electric Corporation, the designer; and Duquesne Light Company, which will operate the plant)

The shipment, originating at Combustion Engineering's plant in Chattanooga, Tenn., had several railroads to move over. Each had its own clearance problems. Dovetailing the preferred routes of each of them was a difficult problem.

At the PRR's Clearance Bureau at Philadelphia, Supervisor of Clearances A. L. Kessler, Assistant Supervisor William E. Walker, Sr., and Assistant Engineer Guy C. Rogers pored over hundreds of charts showing close clearances on the System. Mapping a route for a high-and wide load is always a tailor-made job.

To make sure of what he's doing, Mr. Rogers cuts a piece of graph paper to form the silhouette of the load, precisely to scale. He puts this silhouette on the chart of a tunnel or bridge, to see if it "bumps" anywhere. He does this with chart after chart, through a complete route. One "bump" and the route is out.

Leaving Enola: Three empty flatcars separate the weight of lading and locomotive

|

|

Taking a silhouette of the atomic reactor through this process, the clearance men were able to work up a satisfactory route beginning at Hagerstown, Md., to which the shipment would come via the Southern and the Norfolk & Western. From Hagerstown, the shipment would have to wander a roundabout path through the Philadelphia, Northern, and Pittsburgh Regions.

Lock Haven: At dawn, after night layover, train gets servicing by Clair F. Shaffer

|

|

On Sunday, September 30, the atomic vessel with its massive nozzles, looking like a movie version of a space ship from Mars, rolled into Hagerstown Yard behind an N&W steam engine. Promptly PRR Gang Foreman Glenn E. Robinson and Car Inspector John R. Fouke went at the big I(,ad with their measuring sticks. Sure, the manufacturer had already measured it, and so had the connecting railroads; but the PRR men preferred to rely on their own eyes. How did they know the load hadn't shifted? A sideways movement of one inch could be enough to stymie the whole movement.

Mill Hall: A move past a train on siding is sharply eyed by Conductor H. E. Duey

|

|

But the measurements checked exactly right. The train was then quartered for the night-as was done daily along its route. Orders were for movement only during daylight insofar as possible, as an added safety measure.

West of Altoona: Asst. Foreman R. O. Patterson watches close clearance at rocky cut

|

|

At sunup Monday, the train was on the road behind Engineman George B. Livingston's diesel. He went up the Cumberland Valley branch to Lemoyne, Pa. Here a turn to the west on a wye track brings a train straight into Enola. But things weren't that easy for the big load: a narrow rock cut blocked it. The train had to turn east, go 13 miles on number 1 track to Cly Tower, cross over to Number 4 track, and come back to Lemoyne, this time on a track with plenty of clearance. It was a 26-mile detour to go an actual distance of 200 yards.

This move had been worked out by the clearance men. Their instructions for every part of the route were detailed and emphatic. Examples: "Must run eastward track to avoid station shelter at Sunbury. ...Avoid Williamsport Main Line; must run Linden Line. . . . Must run westward No.2 freight track with care under 17th St. bridge at Altoona. . . . Run No.3 track with extreme care 5 MPH thru Gallitzin Tunnel. . . . Must stop and proceed with hand signal not exceeding 5 MPH under overhead bridge No. 246.61."

Gallitzin Tunnel: Clearance data promised safe passage, but double-checking never hurts.

Lookouts are C. H.

Doran, Westinghouse; P. W. Kaufman, assistant trainmaster

|

|

A car inspector rode the train at all times, eyes on the load. At close spots, others joined his vigil-train crew members, assistant trainmasters or other supervisors who rode different parts of the route, and representatives of Westinghouse and Combustion Engineering who accompanied the shipment in an extra cabin.

The load cleared every tight spot-except one unforeseen one. Just 23 miles short of destination, a boxcar on a siding had its hips stuck out too far. A quick switch got it out of the way.

The train rolled into the power plant grounds at Shippingport on Saturday afternoon, October 6. 11 had traveled six days and 529 miles from Hagerstown. Normal routing would have meant two days and 391 miles.

Shippingport: loud, long, relieved breath from all involved, as big cylinder glides

to plant construction site. PRR revenue including special-train charge was $4,504

|

|

A giant crane lifted the reactor vessel and lowered it into position in the underground complex of atomic apparatus. Soon, the queer shape that became familiar to. so many railroaders will be buried in protective concrete, hidden from human eyes forever, creating nuclear energy and serving as a pilot plant for other cities and more consumers.