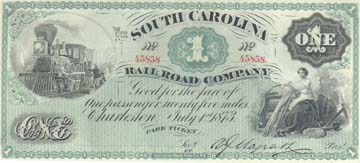

South Carolina Railroad Company Tickets

From Ties June 1955

The Southern System Railway Magazine

Back before the turn of the century a number of railroads, including many lines that later became part of the Southern Railway System, issued fare coupons or notes that bore a strong resemblance to the bank notes then in use. In many cases, this "railroad currency" circulated just like money-as a medium of exchange.

Some of the notes were simply fare tickets, good for the transportation of one or more persons a certain number of miles and deriving their face value from that. Others were printed promises of the railroad to give the bearer railroad service worth a certain amount, freight or passenger transportation or both.

Some resembled bank notes even more closely, in that they were issued in money denominations and bore the promise to pay the face amount to the bearer on demand. The full faith and credit of the issuing railroad and the rail service the company stood ready to perform in exchange backed all of them. The railroad currency about which Ties has the most information is that issued in 1873 by the South Carolina Rail Road (later part of Southern Railway!.

These "fare tickets," as they were called, were engraved and printed for the railroad by the American Bank Note Company in New York and bore a marked resemblance to the bank notes then in circulation. One was the basic denomination, good for the transportation of one passenger 25 miles. (Apparently the mile fare was four cents, which would make the fare ticket worth one dollar.) Denominations of Two, Five, Ten and Twenty had a similar scale of values for the transportation of one or more persons.

"Railroad tender" in South Carolina was a natural outgrowth of the times and the circumstances. At a time when the bank and stock market slump of 1873 made borrowing money difficult, the South Carolina Rail Road was finding only limited success with a plan (started two years earlier) to float a $3 million coupon bond issue to improve the financial position of the railroad and bring in some needed cash.

But if the South Carolina Rail Road couldn't borrow money directly, it could always have some printed and back it with service. Although the exact figure is not available, it seems likely that the initial issue of this fare ticket currency in July, 1813, amounted to at least $75,000. At any rate, there was $68,400 worth of fare tickets outstanding at the end of 1873, according to the road's annual report, and some of it must have been exchanged for transportation. It seems likely that merchants in South Carolina were accepting these "promises to transport" of the South Carolina Rail Road as legal tender. A Charleston newspaper-the '"News and Courier"-offered to accept the railroad tickets in payment for subscriptions or advertising. Money was money whether it was backed by silver in the government treasury, by deposits in local banks or by the guarantee of an equivalent value in transportation.

How much of this railroad money the South Carolina Rail Road actually put in circulation is not known with certainty. The largest amount carried on the company's books at any one time was $97,736 worth that was listed as outstanding at the end of 1815. By the end of 1877, however, only $32,542 worth of fare tickets still remained unredeemed. Apparently those were either exchanged for transportation service or tucked away as souvenirs. The item "fare tickets" doesn't appear after that on the railroad's book.

Actually, the issuing of fare tickets was the equivalent of borrowing money, for it represented a way of getting present cash for transportation service to be provided on request in the future. "Railroad currency" and the use made of it highlight something about money that is frequently overlooked. Money, as pieces of paper or as metal coins, has little or no value of its own. You can't eat it, you can't wear it, you can't build anything with it. Money is only valuable because of the goods and services it represents-in other words, because of what you can buy with it.

Money serves as a convenient medium of exchange so that one individual in a complex society can exchange the goods he produces or the services he gives for other goods and services he needs that are produced by others. Business and industry have grown so complex it is not possible for a man to exchange directly what he makes for what he needs. For example, thousands of men and women map cooperate in making one finished product like an automobile or in providing one service-railroad transportation.

So money provides a convenient method of keeping score. And although it is backed nominally by silver in the government treasury or by deposits in federal reserve banks, in the end goods and services must back money or it is worthless. In that very real sense, these railroad tickets were money.